When Faces Fade: A New Approach to Detecting Alzheimer’s Early

Breakthrough EEG method spots subtle facial processing problems long before memory fails.

In the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease, it's not always the forgotten names or missed appointments that raise the first red flags. Sometimes, it’s something more intimate — like struggling to recognise a loved one’s face.

That quiet but deeply human symptom — face blindness — is at the heart of a bold new approach to diagnosing Alzheimer’s earlier and more accurately. Using a combination of facial recognition tasks and electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring, researchers have found a way to detect disruptions in how the brain processes familiar faces — even before full-blown memory loss sets in.

This isn’t just another memory test. It’s a window into how the brain sees, feels, and fails.

The Experiment: Reading the Mind, Frame by Frame

At the centre of this study is an unusual test subject: a 69-year-old woman referred to as PATIENT(A). Although still articulate and self-aware, she had begun struggling with something most people take for granted — recognising faces of relatives, neighbours, and even her own reflection.

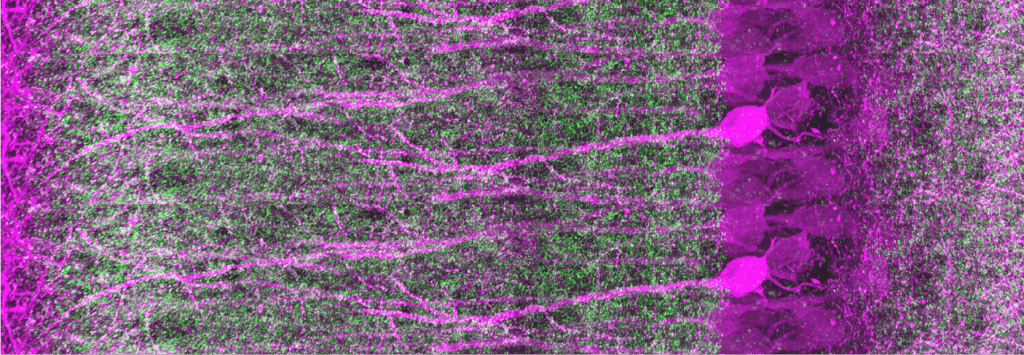

To uncover the “why”, researchers didn’t just rely on conversation or questionnaires. They strapped on an EEG cap and presented PATIENT(A) with a series of faces — some familiar, some not — all while monitoring the brain’s electric response in milliseconds.

They weren’t just looking for if she recognised someone. They were looking at how her brain tried to.

Inside the Brain’s Face-Reading System

When a healthy brain sees a face, a well-choreographed set of electrical signals fire off — including signature pulses known as N170, N250, and N400. These “event-related potentials” (ERPs) are like neurological footprints that show whether the brain is picking up shape, emotion, or identity.

In PATIENT(A), the signals told a very different story.

Her N170 response — typically stronger when seeing faces versus other objects — was noticeably reduced, especially for upright faces. This suggested a basic problem in how her brain encodes the structure of a face at all. Unlike the control group, she didn’t show the usual “inversion effect”, where upside-down faces trigger stronger brain reactions because they’re harder to process.

In short: her brain wasn’t reacting to faces the way it should.

Yet, intriguingly, her N400 signals still lit up for familiar faces — even if she couldn’t consciously name them. That meant the emotional or semantic trace of a face might still exist deep in her brain, just harder to reach.

Beyond Memory: Toward a New Type of Diagnosis

What this research uncovered was a subtle but crucial distinction: facial recognition problems in Alzheimer’s patients may not always stem from lost memory — they might be perceptual, tied to how the brain processes shapes and features, not just names and facts.

Why does this matter?

Because EEG can detect these perceptual problems early — before more obvious memory symptoms arise. That opens the door to early intervention, targeted therapies, and more precise classifications of Alzheimer’s subtypes.

In clinical terms, it also helps answer one of the toughest questions in early dementia diagnosis: is the brain struggling to see or to remember?

A Tool for the Future of Care

While this study was limited to a single patient, the implications are broad. If replicated on larger populations, this dual-method approach — combining behavioural face tests with real-time brain monitoring — could become a standard screening tool in neurology clinics and memory care centres.

Imagine a world where doctors could detect Alzheimer’s before it silently reshapes a person’s identity. Where recognising a face — or failing to — could lead not to heartbreak, but to hope.

This isn’t science fiction. It’s science catching up with what patients and carers already know: sometimes, the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s aren’t about forgetting what happened. They’re about forgetting who’s standing right in front of you.